Prostitution policy in Sweden

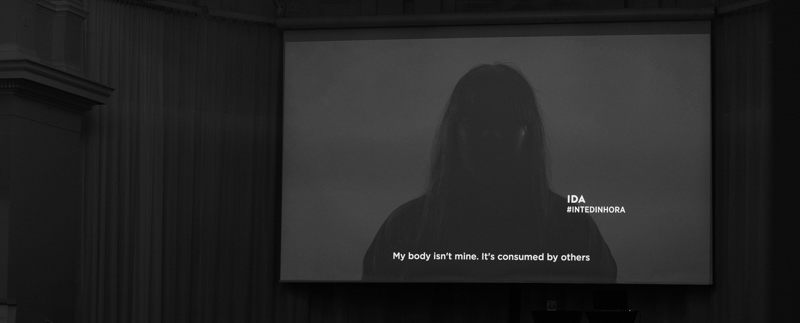

Prostitution is a difficult subject that is not often spoken about in public. It is something that happens elsewhere, to other people. Different countries have taken varying approaches to deal with prostitution, most of these revolving around the criminalisation or decriminalisation of the sale of sex. Then, 24 years ago, something radical happened when Sweden decided to criminalise only the purchase of sexual services. The results are in, and other countries are following Sweden’s lead.

Targeting demand

This new law clearly changed people’s perceptions and shifted focus away from the person in prostitution and towards the buyer of sexual services; the person responsible for prostitution. The decision to address demand was based on a rising consensus with regards to gender equality and a human rights perspective.

Prostitution and sexual exploitation are highly gendered issues. Men are the predominant purchasers of sexual services.

Since Sweden introduced the Sex Purchase Act, several other countries have seen the positive effects of this law and have adopted similar legal frameworks, including neighbouring Norway and Iceland, as well as France, Ireland, Israel, Northern Ireland, and Canada.

The original idea with the introduction of the Sex Purchase Act in Sweden was to increase the agency of the seller, equalise the power balance, reduce the exploitation of individuals – mostly women – and reduce demand. The Swedish government rationalised that it is not reasonable to prosecute the party that in most cases is in the weaker position and is being exploited by others.

The law is also meant to encourage individuals who are involved to seek help in order to leave prostitution, as they can be safe in the knowledge that there will be no criminal consequences of having been involved in the industry. Ending men’s violence against women is a prioritised goal in Swedish gender-equality policy, and preventing and combating the trafficking of human beings as well as prostitution are important steps in achieving this goal.

Statistics show that street prostitution and demand for it have decreased because of this law. This stands in contrast to legalisation and decriminalisation frameworks that have proven not only to increase prostitution but also to normalise the activity.

This legislative approach was totally new and has over the years been complemented by social services, including exit strategies for both the buyer and the person involved in prostitution.

Effects of the law – current situation

Since the legalisation in Sweden went into force, the prostitution market has become global, diversified and virtual alongside other developments in society. It is particularly problematic to accurately assess prostitution in numbers, as statistics are difficult to compare, and figures vary over time as different studies have categorised groups differently. In some studies, the ‘young people’ group can be aged 15–30, whilst the age span can be completely different in other studies.

One certainty is that street prostitution has declined in Sweden since 1995 by more than 50 per cent, though there have been a few fluctuations and a minor recent increase. However, just like in other countries, accessibility has increased due to the Internet.

In 2010, the Swedish government conducted an official evaluation of the law and its effects, and noted the following:

In 2010 the Swedish government conducted an official evaluation of the law and its effects which noted that:

- Street prostitution had decreased.

- The law had acted as a deterrent to prospective buyers of sexual services, reducing demand.

- The law had deterred trafficking, as criminals had not so readily sought to establish organised trafficking networks in Sweden.

- The number of foreign women in prostitution had increased, but not to the extent noticed in neighbouring countries.

- Online prostitution had increased in line with all other sold services since 1999, but not to the extent that it could be said that street prostitution had simply migrated.

- Exit strategies and alternatives had been developed.

- There had been a significant change of attitude and mindset in society.

- Adoption of the law had served as a pioneering model for other countries.

Up until the 1990s, women involved in prostitution were mainly Swedish or came from other Nordic countries, whereas they currently also originate from countries outside the EU.

Findings from 2021

In 2021, the Swedish Gender Equality Agency concluded a governmental assignment to chart the extent of prostitution and Trafficking in Human Beings (THB) in Sweden. The results show a decrease in street prostitution and an increase in websites offering “escort services” and “sugar dating.” The number of children and young adults involved has increased in recent years, one reason being the digital arenas. The statistics according to the latest survey of the Public Health Authority from 2017 show that 10 per cent of men and 0.5 per cent of women have bought sexual services in their lifetime. 1.5 per cent of women have been reimbursed for sex, and the corresponding figure for men is 1 per cent.

National coordination, support programmes and exist services

National coordination

The National Coordination against Prostitution and Trafficking in Human Beings at the Gender Equality Agency, addresses prostitution, human exploitation, and trafficking for human beings for all purposes, including exploitation and trafficking of children.

The National Task Force against Prostitution and Human Trafficking (NMT) is a national platform of governmental bodies working against prostitution and all forms of human trafficking. NMT offers support to municipalities, governmental authorities, and CSOs in human trafficking cases.

In addition to a support line, they have also published National Referral Mechanism: Protecting and supporting victims of trafficking in THB in Sweden. NMT is coordinated by the Swedish Gender Equality Agency.

Regional coordination

Regional coordinators function as a link to social support services and referral in cases related to prostitution and human trafficking. According to the Swedish Social Services Act, the municipality is ultimately responsible for making sure people within the municipality receive the support and help they need. Regional coordinators are partly funded by the Swedish Gender Equality Agency.

Return programme

The Gender Equality Agency furthermore runs an Assisted Voluntary Return and Reintegration Programme for THB victims, operated by the UN Organization for Migration (IOM). Payments to in support of beneficiaries can either be monthly cash allowances or in-kind support such as housing and medical allowances.

Support services

There are several specialist centres and clinics giving support to people in prostitution. Mikamottagningen in Stockholm, Gothenburg, Borås and Umeå, and the Prostitution Centre (Evon House) in Malmö also conduct outreach activities and are mainly staffed by social workers. Buyers of sexual services are provided with counselling at BOSS (Buyers Of Sexual Services) if they wish to receive help to stop purchasing sex. This service is provided in Stockholm, Gothenburg, Karlstad, Västerås, Umeå, Skellefteå, Luleå and Östersund to those over the age of 16.

The Gender Equality Agency and the County Administrative Board of Gothenburg initiated a small-scale evaluation of one of these services in 2020, showing promising results, with a decrease in purchases of sexual services and improved health among the clients. From 2022, a more extensive evaluation of all BOSS services will be conducted. The results will be ready in 2027.

Civil Society Organisations

The Swedish Civil Society Platform against Trafficking in Human Beings is an umbrella platform formed in 2013 to coordinate civil society efforts, identify vulnerable groups and combat all forms of human trafficking. The platform consists of a group of about 20 non-profit organisations and actors, including advocacy organisations as well as CSOs that conduct outreach to victims and provide direct assistance and shelter to victims.

Why Sweden?

Sweden’s prostitution policy and the development of the Sex Purchase Act did not appear in a vacuum but evolved over decades. Direct activism from the women’s movement and the shelter movement in the 1970s and 1980s led to a broader understanding of men's violence against women and society’s reaction to this issue.

It stated that physical violence is closely related to other phenomena in society such as prostitution, pornography, incest, and sexual harassment in the workplace.

In 1977, the Swedish government established the Sexual Crimes Committee. It published two reports: Rape and Other Sexual Assault (SOU 1982:61) and Prostitution in Sweden: Background and Actions (SOU 1981:71). These were followed by the Prostitution Investigation in 1995 (SOU 1995:15).

In 1993, the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health set up the Commission on Violence against Women, which published the Security and Integrity of Women report (SOU 1996:60), focusing on sexualised violence and the normalisation processes of such violence. It noted that physical violence is closely related to other phenomena in society such as prostitution, pornography, incest, and sexual harassment in the workplace.

The proposals in the report were to form the basis of the 1998 government proposition, Security and Integrity of Women (Prop. 1997/98:55). The law on gross violation of women’s integrity is part of the bill, alongside measures against rape and sexual harassment at work. Sweden’s current Sex Purchase Act came about as part of this bill.

A nation dedicated to gender equality

Prostitution and sexual exploitation are highly gendered issues. Men are the predominant purchasers of sexual services whether that service be provided by women (including transgender women), girls, men or boys. Meanwhile, most of the people involved in prostitution as sellers and providers of sexual services are women. That the pioneering Sex Purchase Act hails from Sweden is perhaps no surprise. The social and political climate in Sweden has a long history of standing up against injustices and promoting equality, especially gender equality.

Gender equality has been a political priority in Sweden for over 40 years. A commission for research on gender equality was appointed in 1972, and since 1976 there has been a government minister responsible for gender equality affairs. Since 1971, when a new taxation law meant that married couples were taxed individually instead of as a joint unit, the Swedish government has sought to identify and limit barriers to gender equality so that individuals can be self-empowered and freed from structural obstacles. The taxation law was followed by gender-neutral parental insurance in 1974, under which both parents were entitled to take paid leave for childcare.

The 1970s and 1980s also saw a gradual increase in the participation of women in governmental structures. According to the Inter-Parliamentary Union data presented by the World Bank in 1990, 38.4 per cent of members of parliament were women, and by 1998, the proportion of seats held by women stood at 42.7 per cent. The figure has stayed continually over 40 per cent for the last 20 years.

In 2018, Sweden set a new standard by inaugurating the Swedish Gender Equality Agency. One of the rationales behind this was to respond to the national strategy for combating men’s violence against women and develop knowledge about preventive work. The overarching goal of Sweden’s national gender-equality work is for women and men to have the same power to shape society as well as their own lives.

The Sex purchase act

‘A person who, otherwise than as previously provided in this chapter, obtains a casual sexual relation in return for payment shall be sentenced for purchase of sexual service to imprisonment for a maximum period of one year. The provision of the first paragraph shall also apply if the payment was promised or given by another person.’

If the purchase of the sexual service is from a person of between 15 and 18 years of age, the act is considered as purchase of sexual service from a minor and carries the higher punishment of up to four years of prison.

If the purchase of a sexual service is from someone under the age of 15, the act is considered rape of a minor, regardless of the circumstances.

Trafficking

The Swedish law against human trafficking is based on UN Convention against Transnational Organised Crime, known as the Palermo Protocol, which defines human trafficking as: ‘The recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion. It also includes abduction, fraud, or deception for the purpose of sexual exploitation, forced labour, slavery, or the removal of organs.

Prostitution and human trafficking are clearly intertwined and cannot be viewed as two entirely separated phenomena.

Children's rights

Sweden also has a strong history of pioneering efforts to protect children (another group victimised by trafficking and prostitution). As one example, in 1979, Sweden was the first country to introduce a law against corporal punishment of children.

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, which became effective in 1990, and the optional protocol on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography, which entered into force in 2002, are cornerstones of the international framework on children’s rights. In June 2018, Sweden adopted a bill that incorporated the Convention into Swedish law on 1 January 2020.

The Council of Europe Convention on the Protection of Children against Sexual Exploitation and Sexual Abuse is another instrument that entered into force in Sweden on 1 October 2013. It requires the criminalisation of all kinds of sexual offences against children. It also ensures that certain types of conduct are classified as criminal offences, such as engaging in sexual activities with a child below the legal age, child prostitution and child pornography.

The purchase of sexual services from a minor is, as of 2022, an offence for which there is a presumption of imprisonment. The Convention also criminalises the solicitation of children for sexual purposes (‘grooming’) and ‘sex tourism.’ A new law, violation of a child’s integrity, which came into force on 1 July 2021, criminalises children having to witness violence in close relationships.

The link between prostitution and human trafficking

Prostitution and human trafficking are clearly intertwined and cannot be viewed as two entirely separated phenomena. The driving forces are primarily the same. Socio-economic factors and globalisation trends have given freedom of movement and choice to many, but pockets of poverty, social exclusion and gender inequality have remained or deepened in certain communities.

Self-determination over one’s body is essential in self-care and healthcare alongside sexual and reproductive rights. Total control over one’s own body in a patriarchal system in which men still hold the balance of power is a right that is yet to be fully realised. Prostitution is at the centre of this power imbalance. Political factors in other countries have a knock-on effect globally; instability, conflict, corruption, weakened rule of law and poor governance exacerbate difficult economic situations, especially for women.

Trafficking is a broader phenomenon than prostitution, but an individual can be trafficked for sexual exploitation and the two phenomena are often linked to the same crimes and involve the same actors. This interconnection is further increased with the growth of online prostitution. Parallels can be drawn between advertisements to facilitate prostitution and the online recruitment of victims of trafficking.

International agreements

Sweden’s commitment in the EU, the Council of Europe and the UN additionally inform government policy in this field.

The United Nations

The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) was adopted by the UN in 1979. Sweden was the first country to ratify it on 2 July 1980. Article 6 obliges states to ‘take all appropriate measures, including legislation, to suppress all forms of traffic in women and exploitation of prostitution of women.’

The UN Palermo Protocol for preventing, suppressing and punishing human trafficking, especially that of women and children, is a comprehensive instrument for fighting trafficking. The protocol was ratified by Sweden in 2004. Article 9.5 declares that state parties ‘shall adopt or strengthen legislative or other measures… to discourage the demand that fosters all forms of exploitation of persons, especially women and children, that leads to trafficking.’

Three of the UN Sustainable Development Goals specifically address prostitution and human trafficking. These are: Goal 5 – Gender Equality (target 5.2 to end all violence against and exploitation of women and girls); Goal 8 – Decent Work and Economic Growth (target 8.7 to take immediate and effective measures to eradicate forced labour, end modern slavery and human trafficking and secure the prohibition and elimination of the worst forms of child labour, including recruitment and use of child soldiers, and by 2025 end child labour in all its forms); and Goal 16 – Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions.

The Council of Europe

The Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings was adopted in 2005. It affirms the necessity to act against the demand for sexual exploitation (Art 6) and on the criminalisation of the use of services of a victim (Art 19). The convention entered into force in February 2008 and became law in Sweden in September 2010.

The Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence (Istanbul Convention) is based on the understanding that there can be no real equality between women and men if women experience gender-based violence, and it provides a comprehensive legal framework to tackle sexual violence against women and girls. It entered into force in Sweden in November 2014. The Convention has a monitoring mechanism called GREVIO.

The Council of Europe has another monitoring mechanism called GRETA, which is responsible for monitoring the implementation of the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings. Sweden has undertaken three evaluation rounds by means of GRETA

The European Union

EU Anti-trafficking directive (2011/36/EU) obliges EU Member States to take strong preventative and protective measures as well as increasing the prosecution of trafficking in human beings as a crime. Article 18.1 states that ‘Member States shall take appropriate measures, such as education and training, to discourage and reduce the demand that fosters all forms of exploitation related to trafficking in human beings.’

Article 18.4 states that ‘In order to make the preventing and combating of trafficking in human beings more effective by discouraging demand, Member States shall consider taking measures to establish as a criminal offence the use of services which are the objects of exploitation’.

The EU Strategy towards the Eradication of Trafficking in Human Beings 2012–2016 focuses on concrete measures that will support the transposition and implementation of the Anti-Trafficking Directive, bring added value, and complement the work done by governments, international organisations and civil society in the EU and third countries.

The European Parliament Resolution of 5 April 2011 on priorities and outline of a new EU policy framework to fight violence against women (2010/2209(INI)) recognised prostitution as a form of gender-based violence.

Other EU legal instruments that are important are the Victims of Crime Directive (2012/29/EU) and the European Union Community Directive on temporary residence permits for victims of human trafficking.

In 2016, Europol released a report on trafficking in human beings that clearly states that prostitution is a risk factor for trafficking and that countries where prostitution has been legalised face a higher grade of exploitation. The demand issue and how it is best addressed are also analysed in the European Commission Study on the gender dimension of trafficking in human beings, published in 2016.

Both the Council of Europe and the European Union encourage the creation of National Rapporteurs or equivalent mechanisms and the creation of National Coordinators. Sweden appointed a National Rapporteur at the Police Authority in 1997, and a National Coordinator has been in place since 2009. National Coordination is situated at the Swedish Gender Equality Agency.

Download: Prostitution policy in Sweden

Publication date: 12 November 2022

Last updated: 29 November 2024

Sweden's Consent law

Another well-known Swedish law is the Consent law from 2018. It has catalysed a broader cultural conversation about sexual ethics and respectful relationships. Since it's inception the conviction rates in Sweden have gone up proving that it has been an effective legislative tool to be able to hold more sexual offenders accountable.

Sweden's consent law